The Being Human Institute for early career scholars met virtually in October, 2020 to discuss the essay "Deadlines (literally)" by Rebecca Comay. You can find some of their reflections here.

Deadlines (literally)

In her piece on “the strange temporality of deadlines,” Rebecca Comay posits the deadline as both the product of and a limit to the measurable time of secular modernity. Operating within the standardized calendars and clocks, deadlines objectify the incommensurable temporalities of life (and death) in the service of increased productivity. They quantify social labor time to measure value in keeping with the social relationships governing the exchange of commodities in modern capitalist societies. Comay invokes the Marxian notion of “real abstraction” to describe this political economy and highlights, through her reflections on the Faustian time, its ambivalent secularity. Indeed, with the removal of death’s contingencies, and no longer bound to the retroactive power of predestination’s unknowability on the earthly present, Dr. Faustus’s life becomes a secular experiment. It illustrates “the installation of the ‘homogenous empty time’—the modern ‘merchant’s time’” that seeks to reconstitute human existence as emancipated from the temporality of afterlife and the ever-elusive possibility of salvation (Comay, 21).

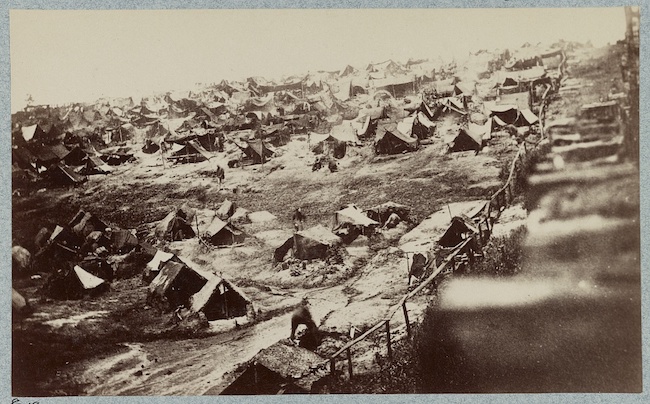

Although very much a product of modern timekeeping, the temporality of deadlines is neither linear and homogeneous nor dead. Its strangeness, Comay further claims, resides in the capacity to linger, to grow, and to overflow the limits that deadlines appear to set within the calendrical time. Indeed, any deadline that structures the modern subject’s social labor time always includes unevenly distributed exceptions in the form of deferrals, extensions, and suspensions. Such exceptions increase, rather than remove, the pressure of the deadline, exposing how it works simultaneously backwards and forwards— “a dialectic of the undead” (Comay, 13). Just as the invisible line in the prisoner-of-war camps of the American civil war that is bound to be crossed in Comay's account, the deadline becomes a spatiotemporal mode of control that constantly undoes itself in order to invite punishment. Its regulatory power comes not from generating the very limit to be surpassed, but from the fact that such limit is often meant to fail in producing the disciplined subjects so that its violence can appear justified.

Academics are quite familiar with the disciplining power and failures of deadlines. But the violence of deadlines does not primarily target modern scholars or normative citizens (that is, the subjects of paperwork, clockwork or intellectual productivity). The effects of such violence are more palpable in the lived experiences of the disenfranchised—to be examined not only spatially as in the case of the “line of death” but also temporally. Consider the refugees and undocumented migrants whose time is constantly appropriated by state institutions and borders through indeterminate periods of waiting, arbitrary detention, and temporary or subsidiary protection regimes (Andersson 2014; Griffits 2014; Ilcan 2020). Although ostensibly contradictory to the bureaucratic machinery of modern states, these measures constitute temporally enforced spaces of exception that render liminality and informality a permanent state of existence in violence for displaced populations (Comay, 6-7). So what work, if any, do deadlines do under such regimes of protracted temporariness?

During my fieldwork along the Turkish-Syrian border in summer 2019, my displaced Syrian interlocutors and I appeared to share the feeling that our time (individually and together) was being wasted because of impending deadlines, albeit of a completely different nature. For me, it was the never-ending deadlines for publications, revisions, grant applications, and the tenure clock that took me away from fully immersing myself in the fieldwork and the demanding relationships that it entailed. For many displaced Syrians, in contrast, “the waste of time” often concerned the paperwork that they needed to complete for access to healthcare, education, and in a few rare cases, citizenship. “Somehow we are always late to submit the documents”, one of my interlocutors noted. It felt to her as if the official deadlines were purposefully set to be missed in order to deter her family from trying to become and act legal. “We are not even told about the deadlines when we interact with officials,” she explained, “and by the time we understand what exactly needs to be done and when, the deadline for submission is usually already over.” Mirroring Comay's reflections, the bureaucratic deadlines in this context punctuated refugee time in a cyclical rather than linear manner: They reinforced the administrative mechanisms of temporal uncertainty through legal arbitrariness that were by no means restricted to refugees and migrants. What the deadlines intentionally or unintentionally produced in the end was not the successful completion of the related task but its recurrent deferral due to random and frequent policy changes.

The stakes of missing the deadline for one's life and livelihood were much higher for my interlocutors than they have ever been for me. Yet ironically, as scholarly deadlines permeated all and not just the academic aspects of my life, my interlocutors described their deadlines mostly as an external source of frustration that ultimately mattered less than their position and obligations within the moral economies of care. Sick and tired of the deadlines that were bound to be missed, for instance, they would often contact a well-connected neighbor who knew a local citizen who knew a lawyer or a state official who could, perhaps in return for some monetary favor, to fulfill a religious obligation, or simply to do good, find the means or persons to make alternative arrangements. After all, what circumscribed the everyday lives and interactions of my interlocutors was not the pursuit of legal existence. It was the social networks and hierarchies, often embedded in the distinct temporalities of everyday hospitality, ritual centered genealogies of religious kinship, and the Day of Judgment, which, to many of them, represented a time of timelessness when social debts would be paid, justice would be served, and their suffering would end. Perhaps we can consider further how such temporalities coexist and persist at the political margins, and how they exceed rather than merely contradict the secular time of modern administrative reason to tackle the predicaments of deadlines for humans under the conditions of our many this-worldly crises.

Seçil Daǧtaș

A few weeks ago, I sat in a zoom meeting. It was a bunch of Ph.D. candidates gathered together to listen to one of the university’s Career Advisors. We were asked to fill out in the shared google doc how we’d felt that week. Very quickly the screen filled up: “fearful,” “anxious,” “dread,” “angry,” “tired,” “that our work didn’t matter,” “helpless,” “depressed,” “fatigued,” “overwhelmed,” one lucky soul who said “things were going great!” And, the last entry: “it feels like time is flying by too fast.”

The speaker ‘appreciated our honesty,’ then launched into a presentation about the sobering reality of the job market - it was bad everywhere; and we’re not trained to transition into non-academic careers; and faculty are imperfect guides even in good market conditions and untrained to support us now. They ended with a pretty decent series of mental health and wellness exercises and a free download to the university’s Breathe “stress management resource” app. We were warned we shouldn’t expect to be able to do all these exercises all the time, but they might at least keep us on the correct side of what they termed the “stress-despair spectrum.” As the meeting ended, they asked to share our thoughts of the presentation on another shared google doc. Only one person responded this time: they said, “make it less like a motivational speech.”

Franz Kafka once wrote a little fable about motivational speeches. It’s about a rat who was put into a maze. It spent its days running and running until it reached the very end, to find that the end contained only a trap. The rat despaired at its unlucky and inescapable fate, until a passing cat took pity and gave it some advice: “You only need to change your direction.” Then the cat ate the rat up.

The university-sponsored Mindfulness App won’t save us. But it does have a “Calming Purrs” music channel.

Anyway, while reading Rebecca Comay’s article “Deadlines, Literally,” this meeting kept playing in my head. Here are a few errant thoughts about why. First, it does feel to me like pandemic time moves faster now with the capricious and cruel effect of “deadlines” tied so clearly to employment and funding (i.e., to health insurance). It is almost banal to note that, of course, dealing with this would be framed by the university in the language of mental health, an issue that the right “mindfulness” exercises can ameliorate, rather than an issue of structural change or institutional mobilization. I could blame university admin. But to be honest, at least they made me an app. Some of the most tone-deaf responses have come from faculty whom have become so accustomed to the reality that most of their PhD candidates won’t ‘make it,’ that they seem completely unfazed by the emergency that now none will. I appreciate moments such as this one that gather together “early career” scholars of varied experiences, because the decision about what type of “late career” scholar we need to become ever more quickly approaches.

Second, I used to be the type to say “deadlines motivate me” – well, they don’t much anymore. If deadlines are arbitrary markers, they are also supposed to be predictive of a result, i.e., if I submit this on time it might get published, if I don’t apply by x I won’t be considered! This predictive capacity, even if it was largely fanciful, now seems ludicrous. PhD candidates have long navigated a system built to produce failure (just look at record levels of journal and job rejection-rates). Perhaps a glass-half-full view of the pandemic’s impact is that this system has not so much finally broken as it has begun working more efficiently than ever before. This is not to say I’m not motivated to do anything at all (don’t worry, I have plenty of fulfilling hobbies). I am struggling however, to act in service of this vocational calling while my motivation is consumed by a burning resentment. If I’ve been shown the map of the maze, why wait for the cat to tell me when to change directions? Having been chasing a notion of success for so long, it’s with a sigh of relief and a twisted smile that I finally give myself freedom to fail.

Gina Giliberti

Rebecca Comay’s “Deadlines (literally)” answers something I was looking for. I have been struggling for some time with a part of my book manuscript in which I trace the temporality of impasse that marks my Syrian friends and interlocutors displaced from Daraa, the city that first dared refuse life of fear under the regime, who now live on the Jordanian border-lands facing Syria, where they may share the same weather with their family still inside, certainly still implicated in what happens there, where the stark difference between “inside” and “outside” Syria acts to confound and abject the work of their lives, still in the shadow of the regime, though they may physically have escaped its reach. Recent ethnographies of humanitarianism (e.g. Feldman’s Life Lived in Relief) have deftly mapped out the contrast between the emergency imaginary of the event and the chronic conditions of endurance, such that humanitarian time oscillates between stasis and crisis, between a flat horizon and the force of decision. But in seeking to write these ethnographic scenes I was routinely frustrated by the lagging sense that I was missing something: the inhuman/intemporal dimension. I had turned to two sites to help face this limit—a Borges short story and a Quranic eschatological figure—but still sought a language to mediate these multiple registers. Such mediation is what “Deadlines (literally)” performs so well (“the spreading capillary tangle”). Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “The Secret Miracle,” first published in February 1943, opens with a Quranic parataxis: “And God made him die during the course of a hundred years and then He revived him and said: ‘How long have you been here?’ ‘A day, or part of a day,’ he replied” (Q. 2:259). In this parable a man—whom the exegetes identify as Ezra the scribe, the Babylonian reformer who led Jewish exiles back to the Levant—passes by a hamlet in ruins. How will God resurrect its inhabitants to life, he wonders. By way of answer, God causes him to die there, to remain dead one hundred years, and then restores him to life, as a demonstration of the divine power. He thinks he was gone a single day, or part of a day. The parable goes on to say that his food and drink were still fresh, showing no sign of decay, while his donkey’s skeleton had crumbled. But then God recomposes the donkey before his very eyes, and he says, “I know that God has power over all things.” God here shows Ezra how the ruins will be restored on Judgment Day and life will return. But resurrecting anything small for the briefest of terms would have served that purpose. Instead God kills and enlivens Ezra himself, has him lie dead for not a minute or two weeks but a full century, and shows him how He can preserve his food and drink in time, frozen out of time, while subjecting his beast of burden to the wear of time. This is a dramatic parable of divine omnipotence, yes, in the sense of Ezra’s proclamation of God “having power over all things,” but more specifically it is a parable of the divine power as it acts on time. It demonstrates the contingency of time, in which the bodies of Ezra and his donkey inhabit asymmetrical positions. The world has its time but God can play with it at will. This is the lesson that Borges takes up and inverts in his short story to which the Quranic verse acts as epigraph. In “A Secret Miracle,” the litterateur Jaromir Hladek is arrested and condemned by the Nazis in Prague. In the ten days between his detention and his appointed death by firing squad, he imagines every possible way he will die. He thinks over the body of work he leaves behind, and deeply regrets leaving his masterwork unfinished. Finally on the night before his death he prays to God that he be granted a year’s more time to complete it. The next morning two soldiers come to take him away; they stand him before the firing squad, and the sergeant calls the order to fire. Then the world stands still. “The rifles converged upon Hladik, but the men assigned to pull the triggers were immobile. The sergeant’s arm eternalized an inconclusive gesture. Upon a courtyard flag stone a bee cast a stationary shadow. The wind had halted, as in a painted picture. Hladik began a shriek, a syllable, a twist of the hand. He realized he was paralyzed. Not a sound reached him from the stricken world.” He first thinks he has entered hell or gone mad, but eventually he remembers his supplication and realizes that God has granted him his prayer. Over the next year he works at completing his unfinished play. He chooses its final epithet—and then, his year of reprieve having elapsed, German bullets strike him down. Once again, the world has its time but God can play with it at will. But in contrast to the Quranic parable, where Ezra was frozen out of time, here it is the world that has been frozen immobile and it is the individual’s time that is extended; it acts as a kind of asymmetrical supplement to the life of the world. In each (in)version, the pedagogic function of the Quranic parable and the narrative arc of Borges’ short story insist that the play of mobility/immobility folds over into another set of coordinates. Comay: “time both contracts and stretches; it simultaneously quickens and thickens” (14). Time is not its own; neither life nor death offers a stable, reliable relation to time. But even granting that fundamental contingency, given the apocalyptic scenes of some of my fieldwork in summer 2018, when the regime was bombarding the south of Syria while my interlocutors’ families fled to the border and hid in the desert, I still felt something was missing. Eventually, working through a series of ethnographic scenes, I turned to the eschatological figure of the dread “heights” (al-a‘raf) to articulate suspension as a form of life. The inhabitants of the Heights in the eponymous Quranic chapter are suspended between Garden and Fire: “And there will be a veil between them. And upon the Heights are men who know all by their marks. They will call out to the inhabitants of the Garden ‘Peace be upon you!’ They will not have entered it, though they hope. And when their eyes turn toward the inhabitants of the Fire, they will say, ‘Our Lord! Place us not among the wrongdoing people!’” (Q. 7:46-47). The exegetes variously identify those “upon the Heights”: many hold that they are those whose virtuous deeds do not preponderate over their vicious ones nor vice versa, and so they remain awaiting their fate. Others understand them as those who have transcended Garden and Fire in their contemplation of the beatific vision. Yet others interpret their position as that of those exempted from the divine reckoning. Their precise identity aside, it is the relationship between their atopic suspension and the striking lucidity it affords which recalls this verse for me with reference to my displaced interlocutors’ inhabitation of the border zone. The inhabitants of the Heights hope and fear between Garden and Fire; they “know all by their marks,” though they are themselves caught in stasis; they have already passed from the realm of the living and so have foregone any means of escaping their fate. They endure the possibility of a divine relief—a possibility that is withheld, not relinquished—and so only “call out to the inhabitants of the Garden” and to their Lord. Likewise, facing the prospective incapacitations of crippling inflation and suspicion (in Jordan) if not outright conscription or detention (in Syria), my friends and interlocutors can only repeat the grim gestures of their immobility. God grant relief, is their refrain—seeking deliverance from immediate predicaments but also from the structuring division of inside Syria/outside Syria which confounds the difference between civilization and ruin, safety and suspicion. Life at the border problematizes (not clarifies) the opposition between inside and outside. Rather than stabilizing or formalizing the flux of everyday life—the older claim of anthropological realism, with its “naturalist” commitments—the eschatological dimension here releases the discipline we uneasily inhabit after the critiques of historicism and sovereignty toward how “the homogeneous continuum of time erupts into a minefield of exceptions” (6). For one of my Daraawi friends, this topological suspension elicits his return to a structured series of memory-images, which I am seeking to write about in this chapter. Images of life and death, which he shows me near every time we meet; images which he laces with new supplications and imprecations: his house and garden; his house and garden ruined; his mosque; his mosque destroyed; his hadith teacher waving at the seashore; his classmate shrouded for burial… These images are clearly neither simply traumatic nor reparative. Rather these inversions of life and death in and against time recall Comay’s Hegelian double lesson: what “appears to be an impenetrable boundary (Schranke) turns out to be a mobile and porous border (Grenze),” certainly, but also that “the dialectic works simultaneously in both directions” (16), time and space become disoriented and stagnant (12). “Even the river flowed backwards” (12). Comay’s essay follows the logic of the limit to where boundaries are eroded. Da ein jämmerliche Dasein fristen, to live on the edge where language is brought to a pitch of intensity and efficacy (a messianic poetics) (15). The splintering into an accelerating series of discontinuous abbreviated tableaux (20). And the paradox of intemporal witness, expressed through three versions in the Quranic verses and Borges play above, by which “the absence of event” becomes “a negative event” (23-24)—what Comay calls “posthumous existence” (26). (For death is not the end.) “Deadlines (literally)” is deeply moving at a rhetorical level, instructive in its cadences, really remarkable. Thank you for the occasion to read it.

Basit Kareem Iqbal

In a wryly titled essay, “Deadlines (literally),” Rebecca Comay uses the concept of the deadline to theorize everything from temporality, to architectural terror, to vampires and the Faustian bargain. Throughout the essay, she considers and reconsiders the work that the deadline does, reminding us of its historical lineage, and returning again and again to consider the many ways prolonged reflection on the concept undoes common sense notions of the term. Importantly, these reflections are undergirded by an emphasis on the coercive nature of deadlines and the ways they distribute privilege unevenly. As she puts it, “time runs out faster, and hangs more heavily, for the dis-enfranchised” (6). This uneven distribution of time and privilege has become even more apparent over the last nine months as the pandemic has slowed time to a halt for some and sped it up exponentially for others.

Writing on time itself, Comay explains that to experience what she terms “pure time” or “time in its unsaturated emptiness” is to “register time’s fracture into a spray of vanishing instants” (23). She proposes that Faustian theatre exists because it is impossible to register pure time in and of itself. The theatre is “literally all about making (by marking) time (23).” These days I feel a lot like Faustus - putting on a show to make time appear. Pandemic time has become, for some, a sort of stretched out, undifferentiated space where nothing seems to be happening. Days pass marked off by meetings, or classes, or meals but they also blur together.

Every day is “blursday.” I must not be completely alone in this feeling because the Washington Post recently sent out an email encouraging readers to sign up for a newsletter titled “What Day Is It? Learn how to recover your sense of time.” According to the pitch, this seven-day newsletter will help readers “learn practices to place yourself in time, try new things and stay connected with the world around you” with the ultimate goal being, not productivity, but resilience.

According to the APA, resilience is “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress” and includes the ability to easily “bounce back.” I half-heartedly clicked “yes” and signed up for the newsletter, knowing I was embarking on another doomed to fail resolution. In some ways, resolutions are like deadlines, once you commit to one it is probably too late to make a difference (13). As I thought of resilience and resolutions, I also thought of Kyla Schuller’s work on impressibility, plasticity, and race in The Biopolitics of Feeling. Schuller explores how biopower governs a “hierarchy that unevenly apportions the capacities of plasticity and determinism among a population” (11). From this perspective, the call to be resilient, to bounce back, participates in the same forms of racialized and classed logics as the deadline. And like the deadline, it always distributes privilege unevenly. The desire (however small) to participate in a project aimed at fostering resilience presumes an affective linkage to other bodies in a similar mileu. It is appealing insofar as it promises connection to a similarly traumatized community and it is problematic because it reinscribes the boundary between those have the capacity for resilience and those whose bodies make that capacity possible for others (Comay 18).

C. Libby

Time runs out faster, and hangs more heavily, for the dis-enfranchised. In other words, the deadline (like death itself) is a ‘real abstraction’. It universalizes itself in a palpably discrepant fashion. The deadline marks the place where the homogeneous continuum of time erupts into a minefield of exceptions.

Rebecca Comay, "Deadlines (literally)"

At the center of Johannes Anyuru’s recent novel They Will Drown in Their Mother’s Tears is a place called “The Rabbit Yard” that Rebecca Comay’s visceral descriptions of the “deadline” brought to mind. A reimagining of Sweden’s Miljonpragmmet public apartments, The Rabbit Yard exists in a near future in which racist-nationalist forces have banished most immigrants from the country and rounded up so-called “Enemies of Sweden.” Part of the pretense for these transformations is a terrorist attack on a comic book store and the Yard is filled with Muslims and their sympathizers. There they are left to pray in the cold on tarps (prayer rugs being banned); their food consists of plenty of pork products (some prisoners’ refusal to eat results in a “layer of grayish squishy meat built up under the the tables and chairs”); prisoners are forced to view cartoons disparaging the Prophet; and children are assigned “free speech coaches” and “democracy entrepreneurs” in order to set them straight.

Readers of the novel get to the Rabbit Yard second hand, however. We read of it in the writings of a young woman, Nour (although there are questions about who she is), imprisoned in a psychiatric facility who believes she has travelled to the novel’s present from a dystopian future where she and her family were kept in the Yard. In the book’s present, it is Anyuru’s double, our protagonist, a writer, Black, Swedish, and Muslim, who fields this woman’s warnings. He is left to measure them against a society which he increasingly distrusts.

There are several ways to think with Anyuru’s novel alongside Comay’s essay. For example, the young woman’s alleged time travel seems to rely upon notions of the strange (a)temporality of trauma to which Comay alludes. Anyuru announces his interest in the psychic effects of trauma and particular forms of power with one of the book’s epigraphs, a quotation from an interview with a former prisoner at the United States’ Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp: “There is no such thing as Guantánamo in the past or Guantánamo in the future. There is no time, because there is still no limit to what they can do.” The prison is, of course, still open.

Relatedly, the time-travelling character and, by extension, Anyuru take on roles that rhyme with Comay’s gestures concerning the Cassandra-quality of every genuine prophecy, Benjamin’s backward-looking angel. Nour—and, again, maybe Anyuru—is warning about something that has in some sense already happened. A future which is already underway—certainly for some. I’m introducing the book in this context, however, to point to how Anyuru’s representations of Muslim being are meant to surface against the violence that They Will Drown presents and predicts.

At one point, as the protagonist is meeting with Nour, she recalls a hadith that they rehearse together, one in which the Prophet prays for God to make it possible for a man who has missed his afternoon prayer to somehow say it “in time.” The protagonist explains, as if filling in Nour’s punchline: “And the sun rose again over the horizon.” He then slips into a voice that addresses the reader directly, “I believe, as many Muslims do, that this actually happened, it’s a historical fact: two men crouching in the desert, the sun rising in the west and making their shadows pull back in, backward into their bodies. Backward into history.” This story surfaces as a point of reference for Nour’s strange account of herself, but the appearance of this image of reversal and return resonates with the protagonist’s articulation of what he knows or experiences as a distinctively Muslim ontology. Elsewhere, he reflects,

I wondered what it was in the human soul that surfaced as an idea about stepping in and out of time, as if moving between rooms in a house. Some sort of dream about nothing being definitive. Outside, post office terminals, roundabouts, and open fields passed by. Do I dare stay in this country? I wasn’t just an origin seeking its future on the Western world’s screens. I was carrying shards of another world, a different grammar in which I ordered space and time. I was Muslim, and it was during those years that I started to think this made me a monster in Sweden.

Part of the book’s drama is this character’s grappling with his own relation to said grammar—the question of inhabiting it against and as a response to a monstrous world.

In other texts, the drama is more explicitly Anyuru’s. In an exquisite essay (trans. Kira Josefsson) about his own relation to Islam, Anyuru describes his appreciation of Islamic ritual as the substance of and media for such otherworldly shards. He writes:

[The body] must be washed in specific ways; it must prostrate itself and lay its head on the ground several times a day; it travels across the world to circle Kaaba. Islam is neither the body’s transcendence nor its opposite, but a different imagination of the concepts of body, I, soul, life, death. This might be why I experience Islam’s physicality as untranslatable: how the body seems to exist inside an iridescent soap bubble during Ramadan, how arms and legs go numb and fill with moonglow during the long night prayers or in the Sufi meditation. How obvious it is, when you wash a dead body in a freezing morgue, that the body is a type of clay vehicle, empty for now.

Beyond the gifts for description in evidence here, if not already obvious, Anyuru’s writing offers much to the student of religion: for example, his insight into the racialization of Islam and his attunment to how such processes braid with psychiatry and the carceral state. These are threads worth pulling.

But here, in conversation with Comay’s provocations, I seek to highlight something slightly different. Namely, I am interested in Anyuru’s interest in how Muslim imaginings of eternity and its lived embodiment might mark alternative relations to the deadline(s)—what the late Charles Long hasreferred to, after Kathleen Biddick, as “‘unhistorical’ temporalities.” Like Long, Anyuru asks us to consider what other routes—suspensions, flights, exceptions—surface within the “minefield of exceptions.”

Andrew Walker-Cornetta