Kaitlyn Ugoretz, University of California Santa Barbara

Torii gate and shrine forest. Source: Your Name, directed by Shinkai Makoto (CoMix Wave Films, 2016).

Kaitlyn Ugoretz, University of California Santa Barbara

Torii gate and shrine forest. Source: Your Name, directed by Shinkai Makoto (CoMix Wave Films, 2016).

What do you know about Japanese religions? And how have you come to know what you know?

As a teacher, a public scholar, and an anthropologist studying the globalization of the Japanese religion known as Shinto, I’ve had the opportunity to ask many different kinds of people these questions. In my grandparents’ generation, folks often mention Zen Buddhism, D.T. Suzuki, and Jack Keruoac’s The Dharma Bums (1958). For my parents’ generation, it was books like Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974) and James Clavell’s Shōgun (1975). Nowadays, with the exception of an occasional reference to Marie Kondo’s philosophy for ‘sparking joy’ through decluttering, the answer is usually the holy trinity of Japanese popular culture: manga (comics), anime (cartoons), and video games. For some, these objects of popular media are simply entertainment; but for others, they are akin to scripture, accessible and ubiquitous ‘texts’ that may be read, interpreted, revered and/or reproduced to enhance their engagement with religion.

I'll be the first to confess that my early interest in Shinto began when I watched the enchanting animated films of Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli. Princess Mononoke (1997) and Spirited Away (2001) introduced me to a whole new spiritual world. Playing the game Ōkami on the Playstation 2, I was introduced to Japanese mythology, albeit heavily adapted. I’ve heard similar stories in interviews and seen it hundreds of times on online forums. While the titles of the shows and games may have changed over the last twenty years, popular media still acts as a gateway for my students into learning more about Japanese religious history and culture. And it’s because of this incredible, ongoing influence of popular media over people’s understanding of Japanese religion that I decided to start my educational YouTube channel, Eat Pray Anime.

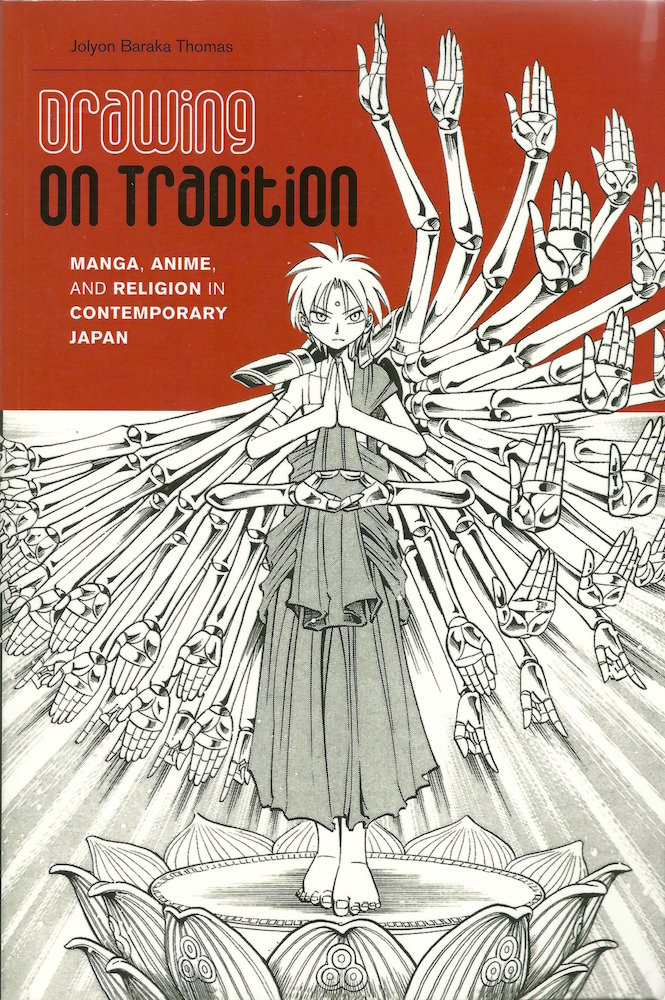

In his book Drawing on Tradition: Manga, Anime and Religion in Contemporary Japan (2012), Jolyon Baraka Thomas examines the complex intersection of religion and entertainment through the lens of Japan. He reminds us that religiously inflected media can fall anywhere on a continuum, from didactic uses of manga and anime by religious organizations to “cosmetic” uses of religious themes and imagery employed to add narrative or visual interest.

Besides the form and content of the media itself, for some, consuming popular culture has even become a part of their religious identity and practice. For example, Jin-Kyu Park has explored how ‘spiritual seekers’ in the United States create their own “spiritual bubble[s]” through their selective viewing of anime that feature imagery and themes from different religious traditions.

Thomas demonstrates how fans ‘entertain’ and ‘re-create’ religion by engaging with manga and anime in religious or ritualistic ways. For example, repetitive viewing of certain films or shows might be considered a form of “ritual performed around a media device.” Fans’ imitation of a scene from Studio Ghibli’s My Neighbor Totoro, in which several fluffy nature spirits and two young girls perform a “prayer-dance to grow sprouts into a giant tree,” brings an originally fictional ritual to life.

Thomas’ work on religious responses to Japanese popular media and my own research on the globalization of Shinto converge around the topic of media as scripture. Thomas writes:

As fans gather around works that they find particularly appealing or inspiring, they may make reading these manga or watching these anime a ritualized endeavor for fan clubs. They may also perform exegetical readings of these products in the fashion of scriptural study groups. As these products—presumably created solely for entertainment—gradually become the objects of this exegetical practice, they take on a greater scriptural character… Indeed, there are examples of manga and anime serving as a gathering point for like-minded individuals, transforming into scripture or liturgy, and giving birth to novel religions. (Drawing on Tradition: Manga, Anime and Religion in Contemporary Japan, University of Hawai’i Press, 2012, p. 91)

In my ethnographic research with transnational Shinto practitioners, often non-Japanese people living outside of Japan who have adopted Shinto ritual practice, I have heard many stories of people who found their way to Shinto through Japanese popular culture. If we may entertain a simple definition of Shinto for now, then let us say that it is a collection of loosely organized ritual traditions centered around the veneration of immanent deities called kami. For my informants, Shinto is a positive, life-affirming, and inclusive religion with an emphasis on gratitude and harmony with nature.

Unlike Buddhism, Shinto does not have a well-defined canon of scripture or ‘sacred texts.’ But that does not mean that Shinto thought and practice have no textual basis. There are texts—part myth and part historical record—that relate tales of the creation of the Shinto deities and the world, centuries-old ritual codices, and histories of the origins of individual shrines. However, familiarity with these texts is not required to visit a Shinto shrine or participate in ritual. Both Shinto priests and laypeople have told me that Shinto is something that is best learned experientially. How, then, do members of online Shinto communities, who may live hundreds of miles from the nearest shrine and each other, come to collectively understand and experience Shinto?

For many, pop culture depictions of Shinto are much more accessible than academic monographs, articles, and sources in Japanese. As part of my research, I trace the formation of a mediatized Shinto ‘canon’ consisting of popular books, anime, and video games. The animated films of Studio Ghibli–and more recently Shinkai Makoto’s works such as Your Name (Kimi no Na Wa, 2016)–are favorites for their explicitly spiritual themes and gorgeous, awe-inspiring depictions of nature. The canon also includes anime that prominently feature Shinto deities, shrines, and ritual specialists, such as Kamichu!, Gingitsune, and Inuyasha. Members sometimes debate which titles are of sufficient depth or merit to be included, with purely cosmetic or ‘disrespectful’ candidates rejected. Through repeated viewing of the Shinto media canon, practitioners reportedly can feel the awe-inspiring majesty of nature, witness and even virtually participate in Shinto ritual and the everyday life of a Shinto shrine, and connect with representations of the divine.

Manga, anime, and video games may be viewed as religious texts or windows into Japanese religious history and culture. But these encounters with religion in Japanese media often lack context. In his book Interpreting Anime (2018), Christopher Bolton reminds us not to miss the forest for the trees when it comes to understanding Japanese culture through anime:

In a very real sense Japanese culture is not a stable, definable, or locatable thing that can explain why anime is the way it is. Rather, what we call Japanese culture is formed through and by a wide range of discourses from inside and outside of Japan, discourses that include anime within them. In other words… it is not Japan that makes anime; rather, it is our readings of anime that constitute our idea of Japan. (Christopher Bolton, Interpreting Anime, University of Minnesota Press, 2018, p. 24)

The same can be said of mediated representations and discourses on religious culture. Anime and video games provide educators with endless opportunities to teach students—and the public— religious literacy: a fundamental understanding of religions and the ability to reflect on how they intersect with all aspects of society and lived experience . However, it is crucial for experts to demonstrate that popular media be used as an entry point into complex topics, but it should not be received as a stable/fixed and literal representation of religion. To get this point across, scholars need to provide historical context and critical analysis of the form and content. In other words, we need to provide exegesis and commentary on mediated scripture. And to do that, we must meet consumers of popular media where they’re at–in this case, through video. That is where my work with Eat Pray Anime comes in.

Over the last two years, I’ve been able to teach thousands of viewers, even tens or hundreds of thousands on a very good day, through my work on YouTube. On top of 50,000 views from subscribers and casual viewers, my videos have been used in college classrooms around the world and even incorporated into US state board of education curricula. So far, we’ve explored complex topics like the religious dimensions of fan pilgrimage, connections between Japanese ritual and theater, and representations of the history of Japanese colonialism in folklore.

But anime is not a special case of a uniquely religious digital medium. Just look at the discussions around the Disney+ streaming series Ms. Marvel and Islam or Ubisoft’s first-person shooter Far Cry 5 and American new religious movements. If people are reading games and videos as textbooks and even scripture, then we as religion educators need to engage them through similar forms of digital media and help provide much-needed context for religious literacy. Of course, that doesn’t mean that we all need to run out and become YouTubers! I’ll freely admit that it is a ton of work and not for everyone. But we can all teach through digital media in our own ways. Here are a few tips:

Kaitlyn Ugoretz is a digital anthropologist of religion and PhD candidate in East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focuses on contemporary Japanese religion, globalization, and media. Her dissertation examines the globalization of Shinto and the growth of transnational digital Shinto communities. Her work has been published in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Japanese Religion, Critical Asian Studies, Asia-Pacific Perspectives, and Religions. She also writes for public venues, including the Washington Post, Religion News Service, and The Conversation. Ugoretz is the Japanese Religions Editor for The Database of Religious History, the first early career member of the Northeast Asia Council's Distinguished Speakers Bureau, an organizer for the GAMING+ Project, and the host of the educational YouTube channel Eat Pray Anime.