Morgan Barbre, Indiana University Bloomington

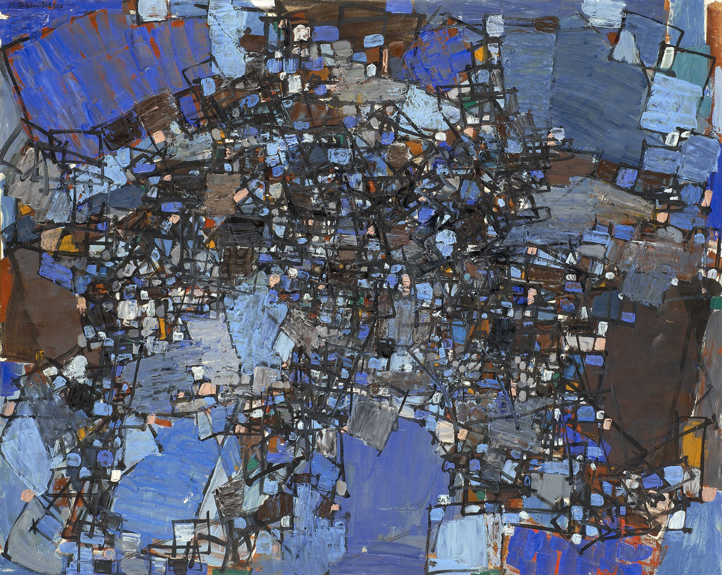

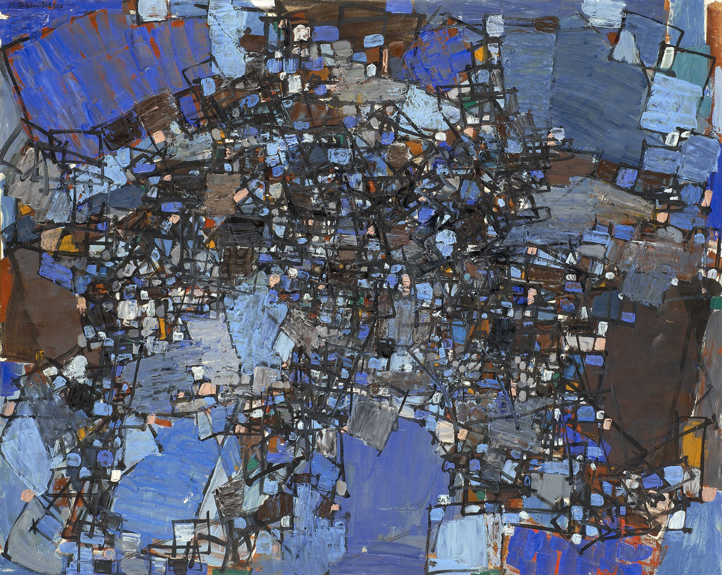

"Galaxy" by Natalia Dumitresco, 1959.

Morgan Barbre, Indiana University Bloomington

"Galaxy" by Natalia Dumitresco, 1959.

We show up to our work and to our students with our whole selves in tow. I am a birth doula. It’s a foundational part of who I am and, and that world comes with me, often in unexpected ways, into the Religious Studies classroom. It’s the scraps of blueprints and the spare parts from which I can draw as I figure out how to be a teacher and scholar of religion in our pandemic-upturned world, an experience that feels a bit like building the plane as we fly it.

In August of 2020—half a year into the COVID-19 pandemic—I moved to Indiana from North Carolina to start my graduate career in Religious Studies. In North Carolina, I had worked as a doula at a local hospital, and by my best estimate I had supported around one hundred births by the time I left for the Midwest. Put simply, birth doulas are companions for pregnant people and their families who are educated in the physiology of birth and breast- or chestfeeding, and provide physical and emotional support before, during, and immediately after childbirth. For many communities, these are emphatically spiritual roles, or roles that protect and carry on sacred traditions around pregnancy and birth, though there are countless philosophies with which one might approach this sort of work and countless ways to be a birth doula.

I worked in a pretty typical labor and delivery unit (as opposed to working in a birth center or in home birth settings), which meant that I interacted with an array of nurses, midwives, lactation specialists, social workers, chaplains, medical students, and physicians in addition to the families and birthing people whose labors I supported. All of us inhabited the birth space in different ways and brought different expertise, though there was plenty of stepping on toes and chaos-fueled confusion in moments where no one seemed able to agree on a path forward. I quickly realized that in my doula practice, I valued two things most: first, holding space for uncertainty and for competing kinds of knowledge (like that which my clients possessed and that of the medical providers), and, second, being a warm and witnessing presence to a birthing person’s vulnerability and strength, regardless of the birth’s outcome. It meant being present for another person’s deep joy as well as for their trauma. It meant listening as a birthing person told me what they felt and knew in and about their bodies, believing them, and figuring out how to bridge the communication gaps between all the constellated knowledge-bearers involved in the sweaty, sticky mess of bringing about new life.

Brigitte Jordan, a German-American anthropologist of birth, thought about these competing claims to reality, and the way that certain claims get privileged over others, in terms of “authoritative knowledge,” or that which wins out as truth at the end of the day. In the birth room, this might look like labels of “real labor” versus “false labor,” or the way that a birthing person’s contractions are graphed on a hospital monitor versus the movements and groans I observe and the things a birthing person says that suggest a far different story than the one digitally depicted. To quote anthropologists Robbie Davis-Floyd and Carolyn Sargent, “The power of authoritative knowledge is not that it is correct but that it counts.”[1] The problem with authoritative knowledge, or at least one of its problems, is that its very construction keeps us from holding many ways of knowing in conversation. And the costs of misusing authoritative knowledge or allowing it to go uncritiqued are high in the birth space. As maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States remains three times higher for Black women than for white women, birth stories like that from Professor Tressie McMillan Cottom help us understand just how vital it is for birthing people to be believed and treated soundly.

These issues are familiar to the Religious Studies classroom, particularly concerning discussions around power, positionality, religious world-making, and the things people call “true.” When teaching religion, we are tasked with modeling what it means to take seriously the things our subjects say, believe, and do, even when our own understandings of the world or our access to sensorial data give us pause or refuse us the alluring satisfaction of empirically verifying our subjects’ claims. And we are similarly tasked with identifying when it is our subjects who wield authoritative knowledge and obscure, often violently, the experiences and suffering of others. The stakes are high here, too.

Understanding birth helps me navigate those conversations about religion and epistemology in the classroom. Yes, I can and do talk about theory in the vocabulary of our discipline, but I also can also talk and teach about theory in the vocabulary of my life by way of talking about (or with) birth. At the very least, my doula work gives me a concrete example of the phenomena that center so many of the conversations we have in Religious Studies: I have seen authoritative knowledge crystalize in the moment when someone’s claim coheres as truth, and, simultaneously, when another’s claim goes disbelieved, often in the span of a single contraction. Birth work is a metaphorical resource from which I can pull. It's a kind of autotheory and a way by which I better understand what we as scholars (and students) hope to talk about when we talk about religion. Teaching with my birth work, to my students’ great relief, doesn’t entail weekly conversations about dilating cervixes or the complicated relationship between midwifery and obstetric medicine in the United States. Rather, it leads me to develop a pedagogical practice that incorporates the tendrils of my birth experiences—what birth and birthing people have taught me about knowledge, uncertainty, and the real—into how I talk with students about the subjects of our shared study. Such a practice acknowledges the richness that comes from sitting in and with the uncomfortable dissonance of holding many ways of knowing all at once without giving in too quickly to an easy resolution. And it invites students to think with the contents of their own worlds (similarly to how I think about being a doula), to excavate the everydayness of their lives for footholds that provide us unique and invaluable ways to talk about religion and what it means to be human.

[1] Robbie Davis-Floyd and Carolyn F. Sargent, “Authoritative Knowledge and Its Construction,” in Childbirth and Authoritative Knowledge, eds. Robbie Davis Floyd and Carolyn F. Sargent (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1997).

Morgan Barbre is an M.A. student in the Department of Religious Studies at Indiana University Bloomington. Her work considers religion and domesticity in the Americas, particularly the ways women use their labor, their homes, and their bodies in ways they understand as sacred.