M. Adryael Tong, Interdenominational Theological Center

Cultivating Curiosity, or, Why Study Scripture At All?

My students are always shocked when I ask the question, “why study Scripture at all?” Before I began teaching at the Interdenominational Theological Center, an HBCU (Historically Black College or University) Christian Seminary, I taught at Fordham University, which, though Jesuit, was much more secular. For my current students, the question “why study Scripture at all?” sounds almost sacrilegious, as if the mere asking of question were a scandal. It sounds like an attack because, for them, the question has an obvious answer. They’re Christian students at a Christian seminary. For them, the value of the Scriptures is simply assumed. My Fordham students were likewise taken aback, but for different reasons. As a professor in the Department of Theology, the students at Fordham usually expect the required courses in the department to be catechetical––a silly Jesuit hoop they have to jump through before they can move on to the coursework they think is valuable. For them, the thought of a Professor of Theology posing such a question shatters these expectations. I think it is a vital question for all students to ask, to think about, and to answer.

Different people and different publics will have different reactions, thoughts, and answers to the question. But for me, it is precisely this practice of asking, thinking, and answering that is important. It is curiosity itself––both the curiosity that motivates the question, “why study Scripture at all?––and the curiosity that studying Scripture engenders and rewards that is real answer to this question. Because for me, what Scriptures is––what Scripture really is––could be described as humans asking questions, thinking about them and trying to find solutions. Sometimes this process is deep and thoughtful. Sometimes it’s not profound. Yet, I think the real value is in the experience of the process, rather than in its results.

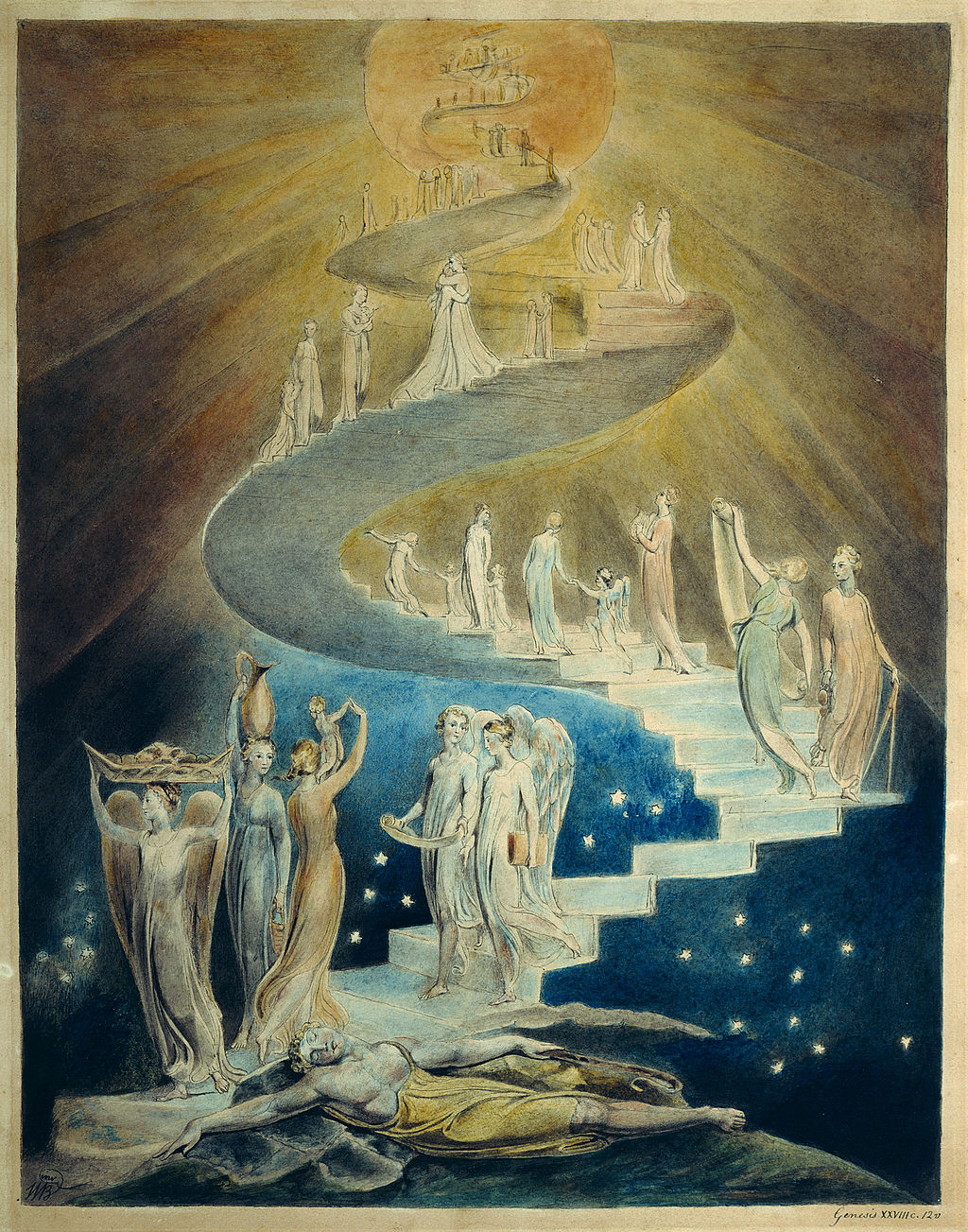

I want to demonstrate this through a short exploration of a section of the Talmud (Babylonian Talmud, Chullin 91b), where the rabbis themselves are studying Scripture, specifically the passage about Jacob’s vision of the stairway (or ladder) to heaven in Genesis 28:10-17. So, in looking at this section of Talmud, we will be studying Scripture (Talmud) studying Scripture (the Bible). The rabbis consider Jacob’s dream and ask of the stairway to heaven, “how wide is it?” Their curiosity about the description of the stairway thus activates our curiosity about why they would ask such a question.

ויחלום והנה סולם מוצב ארצה תנא כמה רחבו של סולם שמונת אלפים פרסאות דכתיב והנה מלאכי אלהים עולים ויורדים בו עולים שנים ויורדים שנים וכי פגעו בהדי הדדי הוו להו ארבעה

The biblical verse states: “And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven; and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it” (Genesis 28:12). It was asked, “How wide was the ladder?” It was eight thousand parasangs, as it is written: “And behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it.” The word “ascending [olim]” is plural. Likewise, the term “descending [veyordim]” is also in the plural. So, altogether there was a total of four angels. [Therefore, the stairway must have been wide enough to accommodate four angels.]

Utilizing a philological argument, they assume there must have been two angels ascending the stairway just as two angels were simultaneously descending it. Since the verbs in Hebrew for “ascending” and “descending” are both plural, they reason that the stairway must have been able to accommodate at least four angels. So far so good. Plural verbs means there must be more than one angel and two angels sounds reasonable for an estimation of the minimum width of the staircase. There needs to be enough space so that two angels can be going up and two angels going down at the same time.

Everything seems perfectly reasonable, but at this point it is easy for the mind to wander. Why does it matter that God created a staircase big enough for two angels to go up at the same time as two angels going down? How does any of this matter?

וכתיב ביה במלאך וגויתו כתרשיש וגמירי דתרשיש תרי אלפי פרסי הוו

It is written regarding an angel that “his body was like Tarshish” (Daniel 10:6). According to tradition, the city of Tarshish was known to be two thousand parasangs wide. [Therefore, in order to accommodate the four angels, the ladder must have been eight thousand parasangs wide.]

The rabbis are relentless in their questioning and answering. They go further. Turning to the description of the angel in Daniel 10:6, they estimate that each angel’s relative size is 2,000 parasangs. Thus, if there are 4 angels on the stairway, 2 going up and 2 coming down at 2,000 parasangs each, then the stairway would be 8,000 parasangs in width. That’s it. The discussion ends. The rabbis move on.

What kind of conclusion is that?

At first glance, the entire conversation seems like an utter waste of time. Who cares if the stairway is 8,000 parasangs wide? What even is a parasang? Why is there math in Scripture? Why does any of this matter?

It is easy to dismiss this entire conversation as idle banter from a bunch of out of touch old men. One can easily imagine a scene of boring old Oxford dons smoking pipes and drinking Scotch while asking one another, “How many angels do you reckon can dance on the head of a pin, old chap?” As the famous line in Macbeth, the Talmudic investigation seems like nothing more than “a tale. Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Yet, half out of exasperation and half out of a desire to put this entire discussion to bed, one might be moved to ask, “Ok, just how big is a parasang? Let’s say, in miles.” A quick search of the dictionary reveals that a parasang is a Persian mile, an ancient unit of measurement. The exact length of the parasang was approximated in many ways, but generally, it was a little over 3 miles. For the sake of simplicity, let’s say a parasang is about 3.112625 miles. Why 3.112625 miles? Well, why not? It certainly fits the description and given the variations in measurements in antiquity, it seems as good of an estimate as any other. Indulge me, and let’s go with it for now.

Unfortunately, it's time for math again. A quick conversion calculation gives us 4 angels x 2,000 parasangs per angel x approximately 3.11 miles per parasang = about 24,901 miles.

So? Who cares?

Well, answer this next question: What is the circumference of the Earth?

Go ahead. I’ll wait.

That’s right.

This seemingly meaningless question and its nitpicky, random answer hid within it one of the most profound theological claims I have yet discovered: the stairway to heaven is the size of the whole world. And thus, according to the rabbinic Sages, every place on earth is connected directly to heaven. When I first did the calculations myself, I was astounded. Speechless. I froze and felt my chest warm as if someone had lit a fire at the base of my throat. My palms began to tingle and the image of the air shimmering gold flashed before my eyes’ imagination. It was as if I could feel the stairway to heaven all around me and within me and through me. To be alive on Earth, the Talmud teaches, means to stand at the base of the stairway to heaven, irrevocably connected to the sublime. The revelation took my breath away.

For a moment, it didn’t matter if I believed in the stairway to heaven, or angels, or even God. What mattered was that an annoying little math problem could contain within it, like an oyster hiding a pearl, a gentle declaration that all around us, everywhere is holy. That, for me, is the magic of studying Scripture.

I can’t guarantee that everyone who reads this article will experience this feeling––or that it’ll happen every time––but what I want to suggest is this feeling I’m describing is attainable by anyone. It doesn’t matter if one is convinced that Scripture is the Word of God or merely the collected ramblings of a bunch of weird old men. The process of approaching Scripture––any Scripture––is to enter into a tradition of humans asking questions, thinking, and then trying to answer them. When we step into that tradition, we become a part of it. It enters us just as much as we enter it. And there, at the intersubjective intersection between the questioning, thinking, answering, hoping, loving, praying, desiring, living, breathing humans of the past, present, and future, amazing things are waiting to be experienced. All it takes is a little curiosity.

M. Adryael Tong, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor of New Testament and Early Christian Scriptures at the Interdenominational Theological Center in Atlanta, GA. She works primarily on the creation of Jewish-Christian Difference through the Parting of the Ways. She is especially interested in the processes by which religious difference becomes inscribed in historical memory as bodily difference.