Aliah Ajamoughli, Indiana University Bloomington

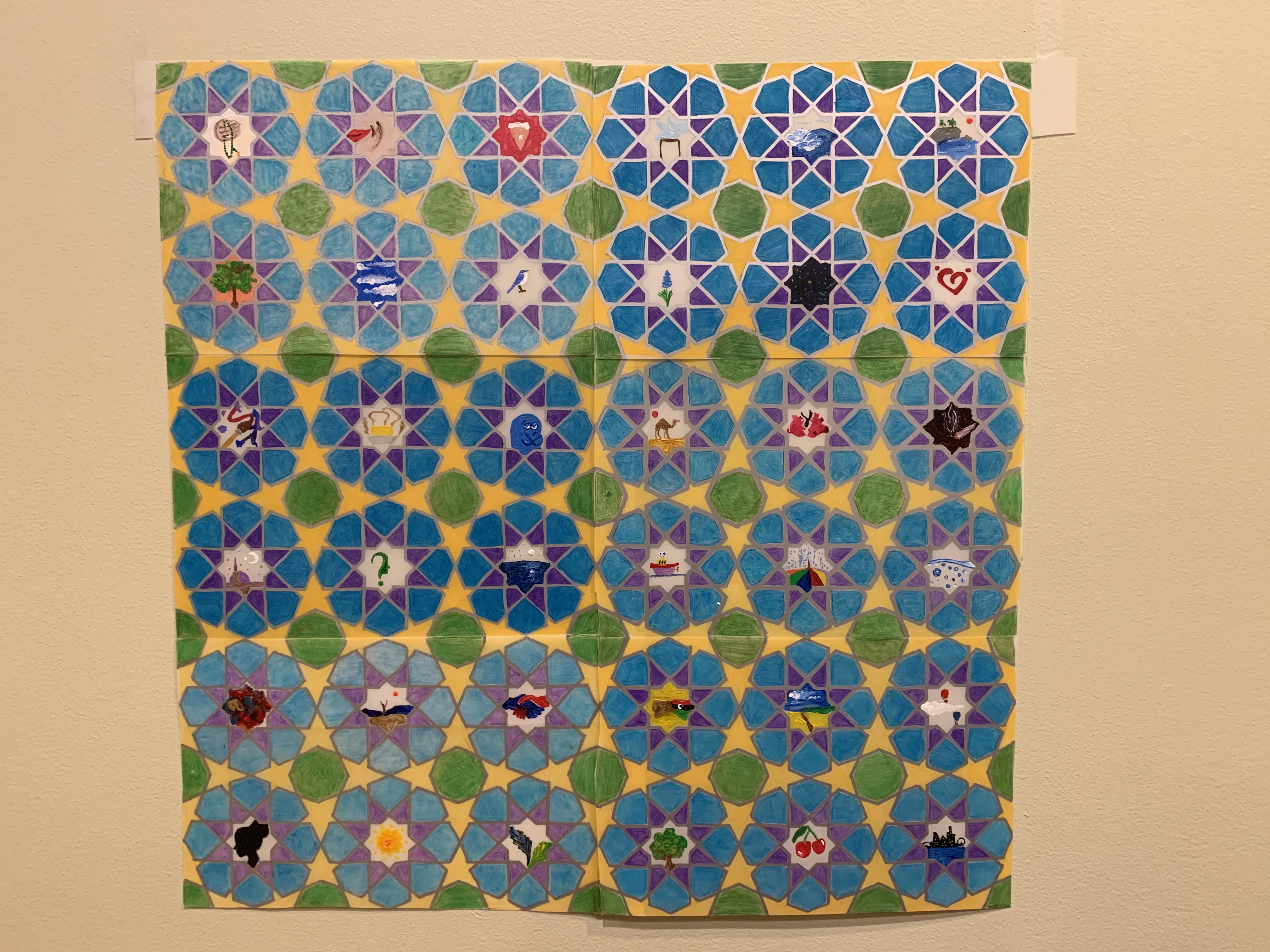

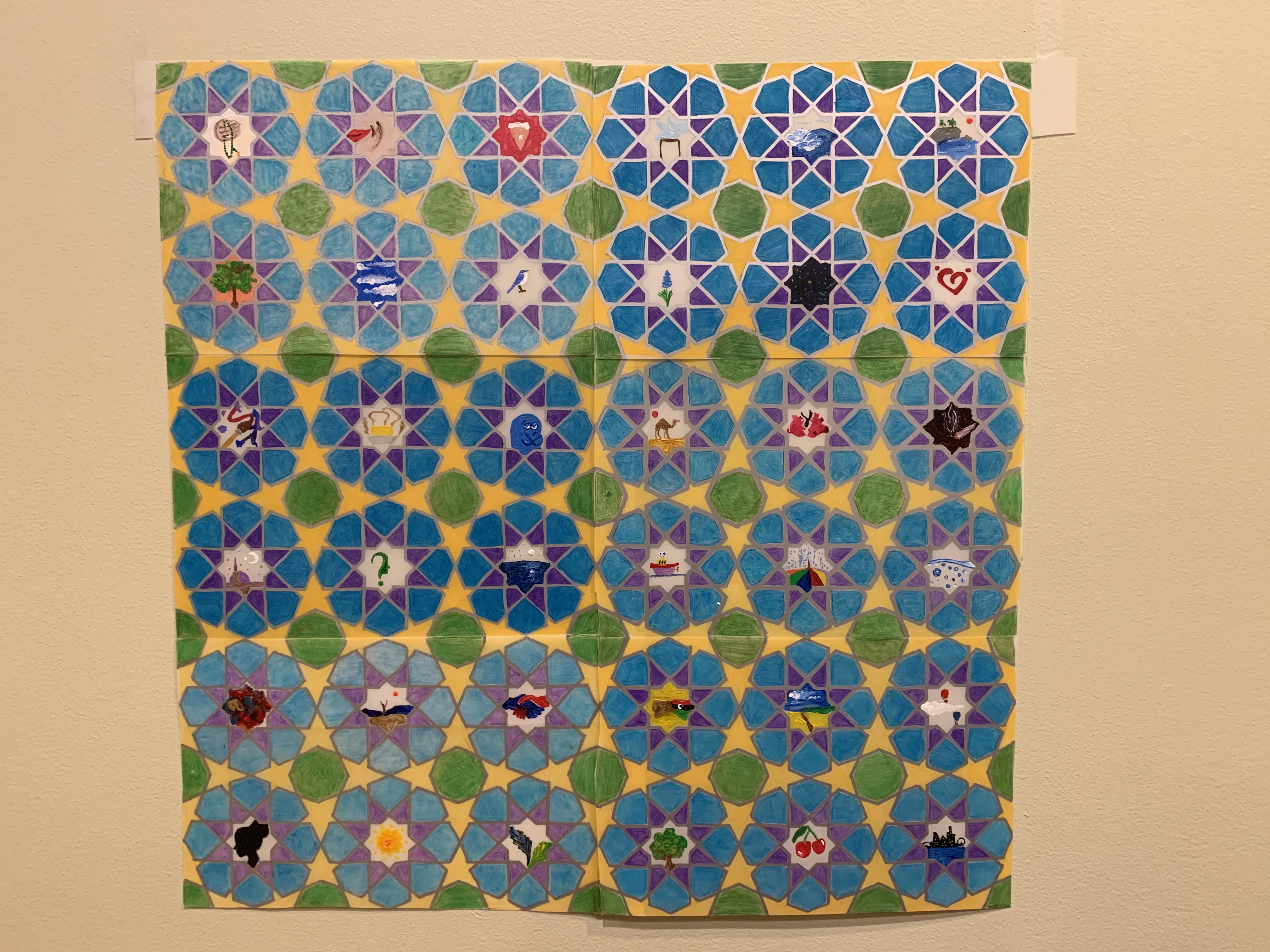

"Tessellated Identities - Life within the Hyphen" by Ariya Siddiqui

Aliah Ajamoughli, Indiana University Bloomington

"Tessellated Identities - Life within the Hyphen" by Ariya Siddiqui

In 2018 after giving a presentation in Chicago on Islamic worship practices, I was approached by an audience member who thanked me for challenging his assumptions about Muslims. Before I could give him a warm smile of appreciation and interact with the next audience member in line, he continued his gratitude by describing his first experience in Southwest Asia and North Africa (SWANA). While on assignment as a federal agent, he was tasked with completing an operation most likely part of the “War on Terror.” Upon arriving at the airport, he heard the athan, or the call to prayer, from every speaker in the terminal. He recalled in that moment interpreting the sound as a war drum preempting an attack on the newly landed Americans and, naturally, drifting his hand towards his concealed gun in anticipation of self-defense. His partner, seeing his fear, gently shook his head no. Understanding the cue, he moved his hand away from his gun and proceeded through the airport with a hypervigilant caution. However, after my teach-in, he now realized that the athan was in fact a call to prayer, not a call to violence.

As an Arab Muslimah who came of age in Alabama post-9/11, this particular response to my public teach-ins on Islam has become a typical reaction. In fact, I have come to expect law enforcement officers and federal agents to reveal themselves in private interactions with me after my teach-ins. Perhaps these federal agents approach me in private conversation because they feel a need to atone for the violence they committed against Muslims, or perhaps they are testing to see whether or not I am interested in aiding them on their next assignment as a “native informant.” Either way, this disclosure is a power move that, whether intentional or unintentional, serves to scare those who explicitly challenge anti-Muslim rhetoric propagated by the state and upheld through mainstream media.

While my fellow organizers and co-facilitators of teach-ins on anti-Muslim racism express discomfort and anxiety when these inevitable interactions with unmarked law enforcement occur, I have come to appreciate this disclosure both in organizing spaces and my scholarly engagements. For my entire childhood, I grew up in a neighborhood in which I received suspicious looks and uneasy gazes for being Arab and Muslim. After my parents sold our childhood home, I learned that two of my neighbors were federal agents: one a retired agent who would sit on his driveway everyday staring at our house from his lawn chair and the other an undercover agent whose cover was blown by the inevitable spread of small-town gossip. Because of this lifelong experience of my family being overtly seen and covertly heard through our tapped phone lines, knowing where the federal agents are in a room almost feels like a privilege that took twenty-plus years of (ongoing) invisible surveillance to earn. Unsurprisingly, this trauma of being monitored at home influences the choices I make as an educator in a classroom infiltrated by systems of vigilance and inspection at play with students, technology, and the institution.

Since scrutiny and examination are such a large component of my experience as Muslimah, I try to integrate these anxieties into my lessons on sound and Islam in the United States. As an ethnomusicologist, I use sound as the conversational foundation for a class of mostly multi-media artists and musicians. To begin these discussions, I play the athan and ask students: how might creators of Hollywood cinema use this sound? Typically, they envision the sound accompanying images of (presumably Muslim) Arab militias holding weapons in the air as they cross a desert landscape. After explaining that the athan is a call to prayer rather than a call to arms, I ask them to consider the implications of associating this sound with terror and violence. Do we identify church bells similarly? Why or why not? In the United States at least, church bells are generally romanticized, associated with weddings, funerals, and holidays. At worst they are depicted as a nuisance because they might chime every hour, but never interpreted as precursors to violence. These contrasting instances of sound and function illustrate how sound can be politicized depending on with which bodies they are associated (white brides or Brown soldiers?). The sounding of the call to prayer is beautiful, unassuming, safe, until it is marked as non-Christian.

Instead of framing these sounds of worship as foreign, I juxtapose them with sounds American students will probably recognize. For example, I play the bent note in blues, jazz, and R'n'B and discuss how their use of microtonal utterance is influenced by SWANA maqam brought to the Americas by enslaved West Africans. I incorporate hip-hop, especially artists thatthat students have probably heard and even sung phrases such as Alhamdulillah and As-Salaam-Alaikum. In picking out these sounds, I mitigate the assumed anxiety of Islam by associating our religious practices with the familiar and, in turn, foster spaces of unlearning. That is, unlearning normative histories rooted in white colonialist understandings of the “Other” and (re)learning histories from the perspective of the “oppressed.” I do not strive to undo the internalizations of anti-Muslim racism we all hold, but instead invite the opportunity to recognize and challenge it as we encounter it inside and outside the classroom.

Another exercise I use when teaching about sound and Islam in the United States is an adaptation of the Creating Cultural Competencies curriculum on challenging anti-Muslim racism in the classroom. Following their “gallery walk” activity, I place descriptions of five policies of federal enforcement and regulation onto the wall: COINTELPRO, U.S.A. Patriot Act, the use of music as torture by the CIA, Countering Violent Extremism (CVE), and the Muslim ban. Students form groups and walk to each station, reacting to each policy with sticky notes. To signal that it is time to move to the next station, I play the song “I Love You” from the American children’s show Barney and Friends, one of the top ten songs played by the CIA to torture prisoners at Guantanamo Bay and a detention centre in Iraq. Music can become a device of torture when played at aurally damaging volumes and psychologically damaging 24-hour loops. While many of these songs were chosen based on what was on the agent’s iPod, “I Love You” has a particular secondary psychological impact with infantilizing lyrics easily understandable to non-fluent English speakers and a repetitive melody that quickly becomes grating after multiple re-hearings.

By conditioning their movement through this song, students are confronted with these state-sanctioned techniques of aural and psychological torture. For the creators of music and art in the room, we question how they would confront the misuse of their creations by federal agencies. In comparing this concern to the paranoia Muslims experience in the marking of their daily actions as “suspect,” this exercise allows students to make connections to the lived experiences of surveillance felt by Brown and Black Muslim bodies stretching from the earliest enslaved Muslims in the United States to the . However, this exercise is not without difficulty. When I implement it in the classroom, I am usually challenged by non-receptive students who attempt to mock the activity. Given the privilege of anonymity, several students have used the sticky notes to describe certain songs on the music as torture lists as a “bop” or to write threatening phrases such as “kill Joe Biden and Donald Trump.” These inappropriate comments, particularly the last, can feel like intentional attempts to mark me as a “suspect” instructor who encourages violent dissent in her classroom. In these moments of subversion and mockery, I find myself falling back into the systems of surveillance that I actively organize to abolish. They become points of activation in which I (re)live the covert regulation of my childhood and, in an effort to find safety and control, obsessively strive to uncover the authors of these anonymous posts—subconsciously correlating them to my undercover federal agent neighbors. After the first use of this exercise, I cross examined the handwriting on these sticky notes with other submitted, non-anonymous handwritten work to “discover” the culprit. Soon after I had begun to decipher the writing, I stopped and asked myself: how can I claim to challenge institutions of surveillance while needing to scrutinize my students in order to maintain trust?

One of the primary difficulties in teaching while Muslimah is to avoid enacting the same methods of surveillance I experience(d). While it is tempting to fall deeper and deeper into systems of classroom vigilance to establish order, I actively challenge myself to abolish supervision and inspection. I work against internalizing the unproductive criticism and subsequent anti-Muslim violence I experience teaching while Muslimah and instead focus on uplifting those students who experience this violence in different contexts all over our campus. Rather than tracking the anonymous authors of negative post-its, I charge myself with a list of goals and strategies to advocate for my Muslim students—one which I reflect on and add to each semester. They ask: how can we explain to the administration the need for accommodations for students fasting during Ramadan? How can we organize to normalize the need for personal space to perform our five daily prayers on campus? How might we instill a sense of pride, not shame, in the audible articulation of our identities as Muslims in the classroom? By asserting my identity as a Muslimah within the ivory tower—as an educator, student, and scholar—I can model ways for other Muslim scholars to navigate the world of academia with greater ease and confidence. Further, when I elevate and support Muslim students, I can create a more welcoming environment that necessitates unlearning negative and harmful associations of other marginalized communities.

My experiences of surveillance as a Muslimah have both created and recreated my pedagogical choices. For me, the best way to heal those wounds is to prevent the trauma of militant scrutiny, supervision, and inspection in my classroom.