#HonorAsianWomenSyllabus: A Critical Religious Studies Approach

Mihee Kim-Kort, Indiana University

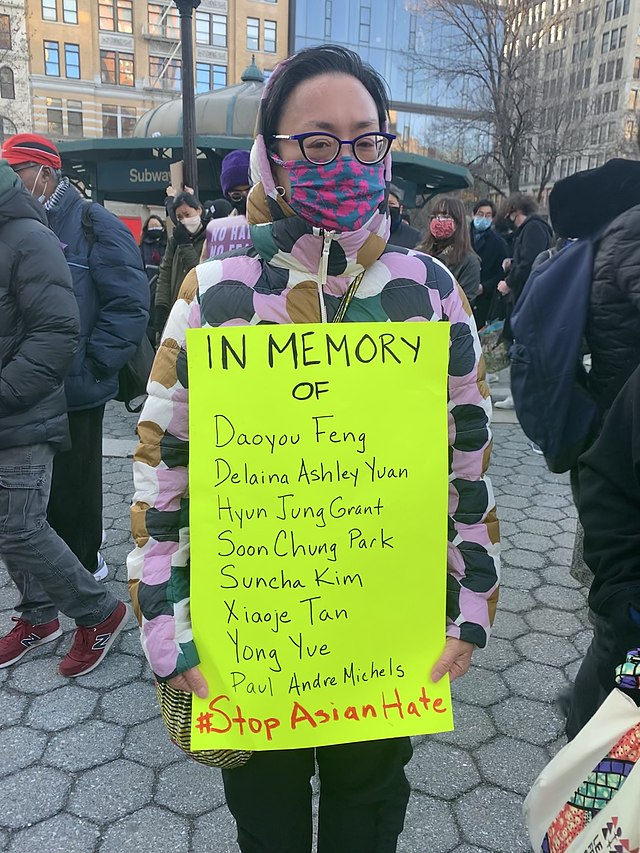

Rally in Chinatown photographed by Andrew Ratto. Spring, 2021. Cropped.

Mihee Kim-Kort, Indiana University

Rally in Chinatown photographed by Andrew Ratto. Spring, 2021. Cropped.

On March 16, 2021, a series of mass shootings occurred at three spa businesses in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. Eight people were killed, six of whom were Asian women, and one other person was wounded. During this past year, the research released by the organization Stop AAPI Hate noted that the number of hate incidents reported to the center increased significantly from 3,795 to 6,603 during March 2021. These six women added to the count:

A 21-year old white man was taken into custody later that day. After the shootings, he was charged by the Atlanta Police Department and the Cherokee County Sheriff's Office. News media were quick to highlight the Cherokee County Sheriff's Office Captain's denial of racist motivations. Acting as a spokesperson for the case, the captain had made the following statement to reporters: "He was pretty much fed up and kind of at the end of his rope. Yesterday was a really bad day for him and this is what he did." According to police, the shooter was motivated by a sexual addiction that was at odds with his religious beliefs and had previously spent time in an evangelical treatment clinic for sex addiction. However, this kind of violence is never committed in isolation—it is undeniably intertwined with long histories of anti-Asian hatred and misogyny in this country. Anti-Asian racism has long been a part of U.S. American history from tropes about disease and contagion to immigration exclusion acts targeting Chinese women to displays of Filipin@s at world fairs or the persecution of the Japanese during WWII.

Asian American studies scholars often explain that Asians are racialized in the U.S. in three ways—the Asian in America is seen as the “yellow peril,” “perpetual foreigner,” and “model minority.” All three contribute to how the U.S. has figured the Asian in America, as cultural theorist Lisa Lowe explains, “Asia has always been a complex site on which the manifold anxieties of the U.S. nation-state have been figured: such anxieties have figured Asian countries as exotic, barbaric, and alien, and Asian laborers immigrating to the U.S. from the 19th century onward as a yellow peril, threatening to displace white European immigrants.”[1] Likewise, the “perpetual foreigner” is used to explain the ways the Asian “is an eternal alien to whom such an understanding is permanently beyond reach.”[2] As the U.S. engaged its neighbors across the “Pacific Rim'' through waves of migration from East/Southeast Asian countries, it had to contend with its ultimate discomfort with but desperation for this cheap labor force. Elaine Kim explains further that the representation of Asian Americans as the relentless, persistent foreigner served as a way for non-Asians to “contain the foreign and heathen qualities” of those who are of Asian descent by making the status of all non-whites unstable and questionable. She describes at length the relationship between "Asians and Anglos": “there are two basic kinds of stereotypes of Asians in Anglo American literature: the 'bad' Asian, which includes the sinister villains, brute hordes, uncontrollable, and those who need to be destroyed, and the 'good' Asian, which are those who are helpless heathens to be saved by Anglo heroes or the loyal and lovable allies, sidekicks, and servants."[3] Finally, the construction of the model minority is based on a narrative of the “successful” assimilation of the Asian in America—an image often embraced by and perpetuated by Asian groups for its “positive” characteristics. For example, the self-perpetuation of the model minority is enacted by many Korean immigrants and subsequent generations—medical doctors, lawyers, and professors—sought out and contributed to their own integration into U.S. American society in this way.

However, the Asian as yellow peril, perpetual foreigner, and model minority emerge in particular ways as they are projected onto Asian women in America, creating a violence of its own genre rooted in hypersexualization, exoticization, and objectification. One way to understand this phenomena is by looking at what is religious about the figure of the Asian woman, especially as constructed by Christianity. We may begin by looking broadly at history, and highlight the colonizing impact of Europeans who sought to Christianize the inhabitants of the Philippines in the 16th century; the Catholic Church in Korea, which traces its beginning to 1784 when Yi Seung-Hun became the first Korean to be baptized when he traveled to Beijing to receive a formal baptism from a French Jesuit missionary there; in the 19th century, the influence of Protestant Christian missionaries all over the world especially in East and Southeast Asia who actively cooperated with the U.S. Ministry of Labor to recruit laborers for Hawaiian plantation owners; and the subsequent immigration waves from these countries. Especially pertinent here we see how during the mid-twentieth century, American evangelical churches were major sources of aid to countries that were also impacted by U.S. military interventions. Today, according to a comprehensive, nationwide survey of Asian Americans conducted by the Pew Research Center, Christians are the largest religious group among U.S. Asian adults (42%).[4] Indeed, one sign of assimilation into U.S. American culture is the formation of Asian immigrant Christian churches that mirror white American Christian communities.

But, cultivating a specifically critical religious studies approach that is transnational in character creates meaningful space to stage these conversations by connecting numerous points of intersection that are often made invisible by the siloing effects of “area” studies which reproduce hegemonic epistemes.[5] Religion becomes more than a cultural marker or characteristic of these processes of racialization, and specifically hypersexualization, exoticization, and objectification. Through an engagement of the discourses of evangelical purity culture we can see how the figure of the Asian woman in Asia and in diaspora, particularly in the U.S., acts as a canvas on which expectations and anxieties[6] around domesticity, sexuality, and nation-state converge to produce more than a scapegoat, but a particular objecthood and aesthetic[7] that evokes a racialized femininity.

The construction of the Asian woman in America cannot be disentangled from the encounter with the Asian woman abroad. These figures not only reinforce one another but are layered and mapped onto one another solidifying not only national, but racialized and gendered borders. Likewise the ideological notion of purity is ultimately about borders. In American evangelical thought, these borders are co-constructed through the twinned ideals of virginity and heteronormative marriage by perpetuating a morality centered around sexuality and sexual behaviors, especially extra-marital sex. It requires the category of gender as mediated and constituted by the Other, often represented in the female body. All of this is a thread through to the establishment of the nuclear family, but specifically the white Christian nuclear family, and undergirded by the myth of the sanctity of womanhood.

The arrival of Asian women can really be captured as “a genital event,” explains Celine Parreñas Shimizu: “The Page Act of 1875 reflected the fear of Chinese women as a source of contaminating sexuality. That they were possibly prostitutes. That they were possibly going to introduce a polyamorous way of life into the United States at a time when there was a growing influx of Asians to the country. If you look at that law, it's revealing that race has always been tied to gender and sexual difference. That there's a fear of genital sex, and that there's a fear of new kinds of sexual culture that these racialized women were representing.”[8] The figure of the Asian woman, as an example of the racialized female body, is one myth that constructs the borders protecting white womanhood.

The six women who died provide more than separate case studies for anti-asian hatred, the hypersexualization of Asian women in America, or the consequences of evangelical Christian toxic theologies about sex. They are women who died because of the mutual constitution of these larger systems of religion and race. Ignoring or side-stepping this complexity will in the end continue to perpetuate dominant Western epistemes that center a particular subject formation. Anti-Asian hatred is a racial phenomenon, but it is a religious phenomenon couched in notions of assimilation and conversion. Evangelical purity culture articulates a religious perspective and ideology that requires intentionally raced bodies as tangible figures of what is not-pure/not-acceptable. And, the hypersexualization of Asian women in America follows these lines as the product of the intimate relationship between religion and race.

The readings below begin with literature known for its canonical nature in Asian American studies with an emphasis on the perspective of Asian women in America. Each contributes as critique and alternative to the figure of the Asian woman. It is followed by secondary resources on the experience of Asian women in Asia and the Diaspora in terms of labor, beauty, and assimilation. The third section provides resources that highlight theoretical and contextual frameworks by scholars who have long shaped the field of Asian American studies--Anne Anlin Cheng, Lisa Lowe, Laura Hyun Yi Kang. The final section gives resources on evangelical Christianity and the topic of sex and sexuality. My hope in putting these resources in conversation with one another is that it will shed more light on the ways religion, race, and purity are intertwined in the subject formation of the Asian woman in America, and more broadly, how race and religion inform one another.

Cha, Theresa Hak Kyung. Dictée. Berkeley, CA: Third Woman Press, 1995.

A genre-bending poetry collection written by Cha that focuses on several women: the Korean revolutionary Yu Guan Soon, Joan of Arc, Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, Demeter and Persephone, Cha's mother Hyun Soon Huo, and Cha herself. It is considered her magnus opus and found on numerous Asian American literature syllabi and reading lists as well as the subject of a seminal collection of essays theorizing Asian American women and writing.[1]Dictée gives insight into the inscrutability of the Asian female subject in terms that are made legible by colonial grammars. Of note is the figure of the diseuse, one who recites at a distance, like an oracle or perhaps like the shamanistic priestess found in Korean indigenous spirituality.

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood among Ghosts. New York: Vintage International, 1989.

The Woman Warrior focuses on the stories of five women—Kingston's long-dead aunt, "No-Name Woman"; a mythical female warrior, Fa Mu Lan; Kingston's mother, Brave Orchid; Kingston's aunt, Moon Orchid; and finally Kingston herself—told in five chapters. The chapters integrate Kingston's lived experience with a series of talk-stories—spoken stories that combine Chinese history, myths, and beliefs. Kingston’s work offers us thick descriptions of a wide range of voices, and stories full of ghosts and myths and hauntings. These narratives offer a different engagement of Asian female subjectivity that cuts across national, cultural, and religious borders.

Kim, Eugenia, The Kinship of Secrets, London: Bloomsbury Press, 2018.

A story about Najin and Calvin Cho, with their young daughter Miran, who travel from South Korea to the United States in search of a new life. The Chos make the difficult decision to leave their infant daughter, Inja, behind with their extended family; soon, they hope, they will return to her. War breaks out in Korea, and there is no end in sight to the separation. Miran grows up in prosperous American suburbia, under the shadow of the daughter left behind, as Inja grapples in her war-torn land with ties to a family she doesn't remember. The narrative illustrates the effects of war and the impact of transnational estrangements as parallel or twinned phenomena embodied by the two sisters, and a look into the particular effects of U.S. interventionism in constructing Asian womanhood.

Lê, Thi Diem Thúy. The Gangster We Are All Looking For. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003.

The novel is a fragmented sequence of events recounted by a female narrator who tells the stories of her past experiences. The story describes the life of her family in America from the lens of her childhood, but it constantly shifts back and forth between Vietnam, the home of her parents, and California, the home of their present. The novel engages themes of identity, family dynamics, and war through a disjointed narrative of five stories through poetic, liturgical cadences. Most meaningful is the narrator’s voice, and what it suggests about her agency and subjectivity as an Asian woman in America.

[1] Laura Hyun Yi Kang, Kim, Elaine H. Lowe, Lisa; Sunn Wong, Shelley, Writing Self, Writing Nation: A Collection of Essays on Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (Berkeley, CA: Third Woman Press, 1994).

Tu, Thuy Linh Nguyen. Experiments in Skin: Race and Beauty in the Shadows of Vietnam. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

An examination of the legacies of the Vietnam War on contemporary ideas about race and beauty, showing how US wartime efforts to alleviate the environmental and chemical risks to soldiers’ skin has impacted how contemporary Vietnamese women use pharmaceutical cosmetics to repair the damage from the war’s lingering toxicity. In particular, Tu leads us to see skin as “a repository, an alternative archive,” through which Asian women are figured through the intimacies of many continents.

Kang, Milian. The Managed Hand: Race, Gender and the Body in Beauty Service Work. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

This study looks closely for the first time at the intimate encounters across tables at nail salons, focusing on New York City, where such they have become ubiquitous. Kang discovers multiple motivations for the manicure--from the pampering of white middle class women to the artistic self-expression of working class African American women to the mass consumption of body-related services. The Managed Hand invites us to consider how Asian women are figured in relationship to women of other ethnicities, and how this particular labor often exacerbates economic and social disparities.

Yung, Judy. Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese American Women in San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press 1995.

The custom of footbinding is the thematic touchstone for Judy Yung's study of Chinese American women during the first half of the twentieth century. Using this symbol of subjugation to examine social change in the lives of these women, she shows the stages of "unbinding" that occurred in the decades between the turn of the century and the end of World War II. The setting for this history is San Francisco, which had the largest Chinese population in the United States. Oral history interviews, previously unknown autobiographies, both English- and Chinese-language newspapers, government census records, and exceptional photographs from public archives and private collections. Yung gives us a view of how Asian women are incorporated and assimilated into the larger U.S. American body politic--its nuances and flaws.

Cheng, Anne Anlin. Ornamentalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Focusing on the cultural and philosophic conflation between the "oriental" and the "ornamental," Ornamentalism offers an original and sustained theory about Asiatic femininity in western culture. Tracing a direct link between the making of Asiatic femininity and a technological history of synthetic personhood in the West from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century, Ornamentalism demonstrates how the construction of modern personhood in the multiple realms of law, culture, and art has been surprisingly indebted to this very marginal figure and places Asian femininity at the center of an entire epistemology of race.

Kang, Laura Hyun Yi. Traffic in Asian Women. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020.

"Asian women" functions as an analytic with which to understand the emergence, decline, and permutation of U.S. power/knowledge at the nexus of capitalism, state power, global governance, and knowledge production throughout the twentieth century. She specifically proposes “thinking ‘Asian women’ as method” (Ch. 1)––as analytic rather than hapless object of study subject to “empathetic identification with those bodies in pain” (35). Her work is instructive in its focus on “comfort women issue,” especially honing in on topics like truth, reparation, and memorials for our re-consideration, as well as helping us to consider how these systems perpetuate certain patterns of violence towards marginalized women.

Lowe, Lisa. Immigrant Acts: On Asian Cultural Politics. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996.

Lowe argues that understanding Asian immigration to the United States is fundamental to understanding the racialized economic and political foundations of the nation. She discusses the contradictions whereby Asians have been included in the workplaces and markets of the U.S. nation-state, yet, through exclusion laws and bars from citizenship, they have been distanced from the terrain of national culture. A national memory haunts the conception of Asian American, persisting beyond the repeal of individual laws and sustained by U.S. wars in Asia, in which the Asian is seen as the perpetual immigrant, as the “foreigner-within.” She argues that “racialization along the legal axis of definitions of citizenship,” as well as the gendered formations of such racial politics included and excluded men or women from Asia as they attempted entry into the U.S.

DeRogatis, Amy. Saving Sex: Sexuality and Salvation In American Evangelicalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

An exploration of evangelicals' surprising and often-misunderstood beliefs about sex--who can do what, when, and why--and of the many ways in which they try to bring those beliefs to bear on American culture. Demolishing the myth of evangelicals as anti-sex, she shows that American evangelicals claim that “fabulous sex”--in the right context--is viewed as a divinely-sanctioned, spiritual act. DeRogatis elaborates specifically on how “for American evangelicals, sexuality and salvation are closely linked,” and how this fuels much of the outward, public conversations of behavior delineating not only the values of marital sex, but ultimately the evils of extra-marital sex.

Griffith, R. Marie. Moral Combat: How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics. New York: Basic Books, 2017

The origins of the conflicts around gay marriage, transgender rights, birth control, or broadly sex, historian R. Marie Griffith argues, lie in sharp disagreements that emerged among American Christians a century ago. From the 1920s onward, a once-solid Christian consensus regarding gender roles and sexual morality began to crumble, as liberal Protestants sparred with fundamentalists and Catholics over questions of obscenity, sex education, and abortion. Griffith provides a way into numerous ways sex and sexuality as mediated through a specific Christinaity are used to construct the U.S. American subject, and those bodies and identities that necessary for constituting those borders.

Kim-Kort, Mihee. “I’m a Scholar of Religion. Here’s What I See in the Atlanta Shootings,” New York Times. March 24, 2021.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/24/opinion/atlanta-shootings-women-religion.html

An op-ed piece I wrote on the victims of the Atlanta spa massacre to highlight the constitutive nature of religion, race, gender, and sexuality in the U.S.

Moslener, Sara. Virgin Nation: Sexual Purity and American Adolescence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Moslener offers a history of the sexual purity movement of contemporary evangelicalism that goes beyond the Religious Right, demonstrating a link between sexual purity rhetoric and fears of national decline that has shaped American ideas about morality since the nineteenth century.

She explains in the introduction: “In response to the threat of moral and national decline, the movement provides ethical regulations derived from religious values and nationalist ideologies. At this intersection of nation and religion, purity reformers, now and then, employ theories of rise and decline in order to position sexual purity, and the adolescents who embody it, as the greatest hope for restoring America’s lost innocence.” Especially salient here is how post-Cold War contexts were ripe for the “rhetoric of sexual purity, or more precisely a rhetoric of sexual fear, connecting sexual immorality with national insecurity.”

Asian American writers workshop podcast, one of the latest:

https://aawwradio.libsyn.com/crying-in-h-mart-ft-michelle-zauner-hrishikesh-hirway

Crying in H Mart , Michelle Zauner

Asian Americans, PBS series

Seeking Asian Female, Debbie Lum, dir, documentary film

Call Her Ganda, PJ Raval, dir, documentary film